Mechanical

Defects

The

first problems

you'll want to address are any mechanical defects. There are

a few

simple ways to "fix" general problems. Missing parts can be

bought

or created. Keep your eye out for a box or can of plane

parts.

I've seen them at flea markets and if you plan to end up with more

than

one or two planes, they may be worth  the

money. Lost toe adjustment knobs can be replace by knobs

found at

hardware stores. The eccentric lever that moves the

toe in

and out can be replaced with a washer that's been filed to shape

-- something

like this. The lever on the quick release cam, located on

the cap

is sometimes broken. You can drill it out and replace the

whole thing

with a hex screw from the same hardware store. I put a hex

nut behind

my cap for additional support. I filed a "V" in one side of

the nut

so it would fit flush against the bottom of the cap, then tapped

the cap

from the bottom side, so the threads would line up. I don't

think

it really adds much more than a little piece of mind, but I like

it. the

money. Lost toe adjustment knobs can be replace by knobs

found at

hardware stores. The eccentric lever that moves the

toe in

and out can be replaced with a washer that's been filed to shape

-- something

like this. The lever on the quick release cam, located on

the cap

is sometimes broken. You can drill it out and replace the

whole thing

with a hex screw from the same hardware store. I put a hex

nut behind

my cap for additional support. I filed a "V" in one side of

the nut

so it would fit flush against the bottom of the cap, then tapped

the cap

from the bottom side, so the threads would line up. I don't

think

it really adds much more than a little piece of mind, but I like

it.

The

Sole

Fixing

the sole

can be simple or complex, depending on the problems. If I

only have

a few scratches on the bottom of the plane I just level the sole

and let

it go at that. Deeper scratches, in critical areas, require

removal

of more surface and can take a lot more time. Here are some

things

that I DON'T recommend.

Using a belt sander. Unless you can find a belt

girt finer

than 120 I'd skip the belt sander. You can end up with

scratches

as deep as the ones you're trying to remove. If you

do use

a belt sander don't keep at it for long periods of time.

The plane

can heat up and you run the risk of deforming the sole while

it's hot,

and having it change shape when it cools.

Files. If you're going to file the sole down, be

very careful.

I've put extra scratches (some of them deep) in the sole

of a plane,

being careless with a file. Once again, you can remove a

lot of metal

very quickly but you can also remove to much. If you're

determined

to use a file, use it across the sole, not along the sole.

That way

any scratches will create less problems.

Orbital sanders. If you have one on which you've

replaced

the rubber pad with a steel or Plexiglas pad you might be

okay. But

the rubber won't flatten the sole. It will just remove

material.

Again, if you do use an orbital sander, don't use grit that's

larger than

120. Go for 220 or finer. You can end up removing a

lot of

material and still have to remove as much by hand!

Ask me how I know all this.

I finally ended up using a sanding disk that fits in my 1/4 in

electric

drill. It'll remove material quickly and I have a lot more

control

over it than the file. There are some rules I've learned

to follow.

-Only tighten the plane in the vice enough to hold it

there.

Excess pressure on the sides will push the center up and

I'll end up with

a concave sole when I take it out of the vice.

-Keep the sander moving at the same speed.

Don't slow down, don't

speed up. If I do I'll introduce low spots or

leave streaks in the

sole.

-Make a number of passes. Only work on a strip

about 1/4 to 1/2

wide at a time. Don't use a lot of pressure or

I'll be creating work

for myself later on.

-By this time it should come as no surprise that I

recommend using medium

grit sanding disks. (120 or finer.)

-I work both from the front and from the back of the

plane. This

will keep me from creating a set of ridges. Most

planes have a convex

sole.

-After I think I'm through with the grinding, I take

the plane out of

the vice and make a few swipes over my flat

surface and look at the

sole. If there are places that are higher than

other places, they'll

have telltale scratches on them. I go back to

the disk sander and

remove extra metal in these areas. I repeat as

necessary. (I

don't want to over do it, or I'll end up having to

remove metal from places

that were originally too low.)

|

| When I get through I should see fine scratches

in the sole. When

I remove these by lapping the sole will be flat. |

|

You may find that using a file or a stone or a belt (or

orbital) sander

works for you. If so, more power to you. The above

is what

works for me.

The

Mouth.

Chips, scratches or a concave toe at the mouth are some of the

hardest

problems to fix. Examine the area. How deep is the

problem?

If it's fairly shallow, grinding, then lapping the sole may

be all

that's needed. If, on the other hand, it's deeper than I

want to

go with a grinder, my only answer is to re-create the

mouth.

When I do this, I want to go slow. I expect to spend a

lot

of time on this area. Correcting both problems with the toe

and the

back of the mouth will result in the mouth being slightly larger

then it

was when I started.

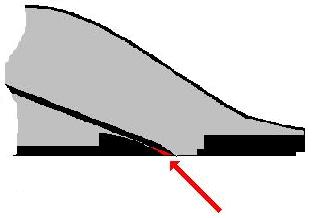

The red arrow points to a problem you

can have if you

don't watch what you're doing.

If you don't hold the file parallel to the work

area., you'll round

the mouth so that it won't support the

blade. The only way

to cure this is to take off MORE metal, making the

mouth longer.

If the toe can't come within a few 1/32 of the blade

you've lost a bit

of the usefulness of the plane.

|

If the problem is in the back of the

mouth, then I have

no choice but to file it down. I use a small fine

cut file.

I can take off a lot of metal in a short amount of time

with a basted file.

I start by disassembling the plane. You can leave

the Iron adjustment

lever if you like, but everything else has to come

off. (You'll have

to punch, or drill the little axle out of the

plane body if you want

to remove the lever. Then you'll have to replace

it when you're done.

Be careful when you're doing this, you're working with

cast Iron and can

damage the frog. I'd follow the Doctor's motto, "first

do no harm.")

I put the file in a bench vice, tilted, back end

down, at about a 20

to 25 degree angle. I make sure I've got

good light.

I work from side to side keeping everything

square. I take my time.

The blade support at the back of the mouth has to line

up with the top

of the adjustment lever. While I'm at it,

I watch that I don't

remove the little fingers off the top of the

adjustment lever. The

end result has to be flat. If it isn't, then

I'll have a blade that

isn't supported at the back of the mount. This

lack of support can

allow the blade to bend in the mouth, causing it to

grab and pull out fibers.

|

The toe is much easier to work on. If enough material wasn't

removed

in flattening, then I remove the toe from the body and carefully

lap the

back side on my flat surface. I keep the back

square. You can

remove about 1/16 of an inch this way. More than that may

result

in a mouth that can't be closed as far as you would

like. I

use this technique for chips, nicks and a toe that's been worn

concave.

The

Toe

If the toe doesn't want to move freely, I remove it from the

plane.

I examine both the sides of the toe and the slot that the toe

rides in.

Look for debris and rust. I clean this area with a

toothbrush and

some WD-40. If this doesn't cure the problem, I use a small

flat

file to carefully file along the inside of the plane.

I Pass

the toe over my lapping surface a few times on each side.

I

want the toe to slide but not be lose.

The overwhelming theme of this entire process is take your

time.

Don't try to hurry the process. Once you've removed

material, you

can't put it back. Too much is too much and may make a bad

situation worse.

Almost all the cleanup and fix up is done by hand. Power

tools can

ruin a project by to quickly removing material. Before you

buy a

used plane with the idea of bringing it up to standards, make sure

you

have the time to spend doing it. |